YAMASHINA HECHIGWAN.

山科 ノ貫

There was a man named Sakamotoya Hechigwan who lived in upper Kyoto and was married to a niece of the famous physician Manase Seikei.

京都の高地に坂本屋ノ貫と言う人が住んでいて、曲直瀬道三の姪婿、曲直瀬 Seikei言う有名な女医者と結婚しておりました。

Originally he styled himself Nyomugwan, but afterwards changed it to Hechigwan, the character read Hechi being half of the character ‘jin' or ‘hito' which signifies ‘man' so one may take it to mean that was about all he considered himself to be.

もともとは如夢観(にょむぐあん:ゆめごごち)と言っていましたが、ノ貫に改名、漢字のノはじん又はひとで男を意味していて、彼は彼自身の事をさしていると思われます。

When Hideyoshi gave his great Cha-no-yu meeting at Kitano in the tenth month of 1588, Hechigwan set up a great red umbrella nine feet across mounted on a stick seven feet high.

太閤秀吉が1588年十月に開催した北野大茶会の時、ノ貫は、高さが七尺(約2m)で直径九尺(2.7m)の赤傘を立て茶の湯を催した事で有名です。

The circumference on the handle he surrounded for about two feet by a reed fence in such a way that the rays of the sun were reflected from it and diffused the color of the umbrella all around.

周りにはアシの垣が約2フィート(60cm)あって、日の光が差し込み傘の色が反射していました。

This device pleased Hideyoshi so much that he remitted Hechigwan's taxes as a reward.

その演出に秀吉は大いに喜び、ノ貫の税を免除したそうです。

Another example of Hechigwan's drollery was this.

ノ貫のお茶目な話があります。

He invited Rikyu to a Cha-no-yu and purposely told him the wrong time.

ある時、彼は利休を茶の湯へ招待して、ワザと間違えた時間を伝えました。

Rikyu arrived at the Tea-room only to find the door shut and no sign of any preparation.

利休が茶室に到着すると、戸が閉まり何の準備もされていません。

So he opened the garden gate and went in to investigate.

彼は庭の門を開け待合へ行って見ると。

Now in front of this wicket a hole had been dug and covered with a hurdle over which the earth had been carefully replaced.

木戸の前には穴が掘られていて網垣がかぶせられ、落とし穴が仕掛けてありました。

Rikyu really knew all about it but walked straight on as though he didn't.

利休は直ぐに気付きましたが、わざとまっすぐに進みました。

Naturally the hurdle gave way and he fell into the hole so that his clothes got all soiled with clay.

必然として、網垣は崩れ穴に落ち、着物が泥だらけになりました。

Just then Hechigwan appeared, apparently much astonished, and apologized profusely.

ノ貫突然現れて、びっくりした様子を見て謝りました。

He then invited Rikyu to the bathroom where the bath was providentially just ready.

利休をあらかじめ準備した風呂場へ。

When he had washed and put on fresh clothes provided by his host he was shown into the Tea-room where Hechigwan treated him with the very greatest consideration, so that the meeting was most enjoyable for both.

すでに湯を沸かしておいて、新しい服をしつらえ、ノ貫が茶室に招き入れました。そこにはとても趣向の凝らした取り合わせを用意していて、二人は茶会をとても楽しみました。

Some time afterwards it happened a certain person enquired of Rikyu what he thought of the assertion that Tea involved servility, and the Master quoted his experience with Hechigwan as an example to the contrary.

その後、この趣向の話を利休から聞いた茶人達の間で「やりすぎではないか」と物議をかもします。ある茶人は、ノ貫をその茶の精神の対局に置きました。

“I had heard of his purpose some time befor,” he said, “but since it should always be one's aim to conform to the wishes of one's host, I fell into the hole knowingly and thus assured the success of the meeting. Tea is by no means mere obsequiousness, but there is no Tea where the host and guest are not in harmony with one another.”

「私はその意図を聞いたが」、彼は続けます。「亭主が客に無理強いをする事、心得顔に穴に落とし、そして接客を成功させる手段としてはいかがなものか。茶は単なる媚びるものではない。変な手段を使って亭主と客の和を演出するのは茶の湯の本分ではない」。

Rikyu's art and his skill in utilizing the device of another are well shown in this answer.

利休の芸術と演出を説明する、とても的確な言葉です。

Hechigwan's intention was to amuse himself at Rikyu's expense, and Rikyu amused himself by the contemplation of this amusement. Rikyu's performance was of a far higher order.

が、ノ貫の意図、利休に対してしてやったりの彼自身を楽しませましたし、利休もわざとひっかった趣向を楽しみました。

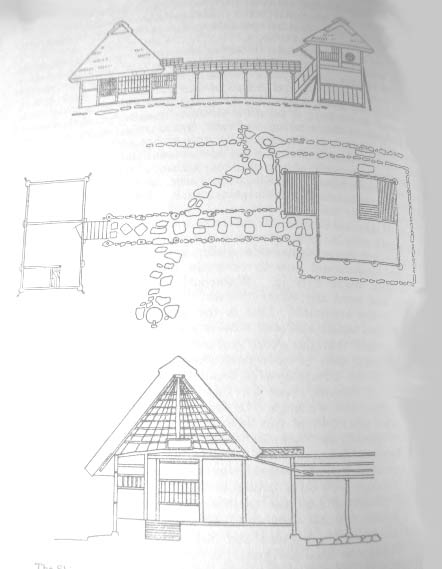

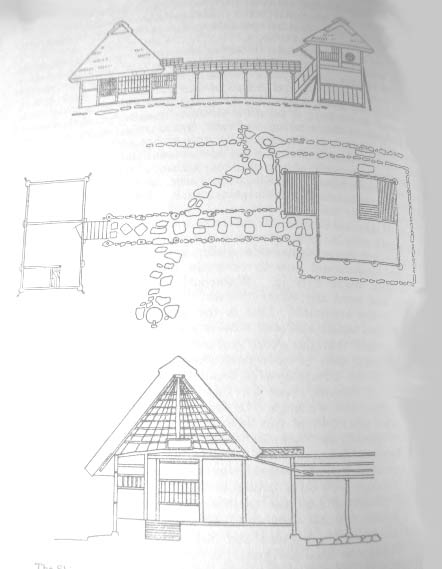

The Shigure-tei and Kasa-chaya, two Tea-rooms connected by a covered way consisting of a roof of bark supported on pillars of natural wood, about twenty-five feet long.

時雨亭と傘茶屋、この二つの茶室は、約8mの木柱廊下木皮屋根で繋がれた建物です。

The Shigure-tei is two storied, the upper part used as a Tea-room and the lower as a Machiai.

時雨亭は二層構造で、上は茶室で下が待合になっています。

These rooms were formerly in Hideyoshi's palace of Momoyama and were designed by Rikyu, but are now in the Kodaiji, Kyoto .

桃山時代の秀吉が建て、設計は利休です。現在は京都の高台寺に有ります。

Elevation and plan with section of the Kasa-chaya, so called because the ceiling is constructed like an open umbrella.

立面図による傘茶屋、名前は傘を開いた感じなので名付けられました。

The Shigure-tei or Autumn Shower Pavilion takes its name from that built by Fujiwara

Teika as a resort for viewing the scenery of the showery season and comwosing verse.

Cf. the No drama entitled Taika.

時雨亭とは秋の長雨の家と言う意味で、藤原定家の作品から引用され秋雨と寂の詩です。

Hiki Hyaku-O once invited Rikyu to tea and served water-melon with sugar over it.

Hiki Hyaku-O、利休を茶に招待し、砂糖をまぶしたスイカを出した時の事です。

Rikyu ate only that part that had no sugar on it and when he got home again said with a smile to his pupils, “Hyaku-O does not understand how to entertain people.

利休は砂糖のかかっていないモノを食べました。帰宅した後に弟子達に絵顔で言いました。「Hyaku−oさんは人を楽しませる方法を知らないね〜。」

He gave me water-melon with sugar over it.

「彼は砂糖のかかったスイカを出して下さったのだが、、、」

Water-melon has its own natural taste.

「スイカはそれ自体が甘い。」

It does not need any other flavor.”

「それ以上の味はいらない。」

Rikyu liked the natural and Hyaku-O the artificial.

利休は自然でありHyaku−oは意図的である。

That is the difference between one who has the real Tea spirit and who has not.

前章の茶の湯の精神を持っているかいないかが解る出来事です。

It is said that the great recluse can live the retired life in the city, but most men of taste prefer to retire to quiet and remote spots, and one of the advantages of this is that they are not very liable to the visits of thieves, since the things they treasure are only old pots and pictures and writings.

こう言えます、真の数寄者は街に住む事が出来て、多くの凡人はむしろ世間から遠く隔離する。その優越の違いとは、盗人が近寄るのを遠ざけるがごとく避ける人か、書画骨董のみに趣向を持っているかに尽きるのです。

If they had money with them they would attract the attention of the light fingered.

沢山のお金があると、人は輝く宝石で身を飾るのです。

There is an example of the poet Botankwa Shohaku who had a hundred pieces of gold stolen while he was living in the Western Hills.

連歌師の牡丹花肖柏(ぼたんかしょうはく)は、西岡に住んでいる時に百両を盗まれた事があります。

Yamashina Hechigwan too once sold his Tea vessels for seventy kwan and kept the money in his cottage. A thief broke in and stole the lot.

山科ノ貫も彼所有の茶碗を七十両で売り、庵においていました。それを一人のかっぱらいが盗んだと言う事です。

So “Safety First” for the man of taste lies in keeping no money in his house. Truly Love and Money are everyone's enemy.

安全第一、家に金は置かない事です。純愛とお金は敵対です。

Yamashina Hechigwan and Rikyu were always rivals on Cha-no-yu.

山科ノ貫と利休は、時として、茶の湯のライバルでした。

Hechigwan was indignant at the everybody flattered Rikyu, and resented the esteem in which he was held by those in high places.

ノ貫は皆が利休に媚へつらう事に面白くありません。特別の存在として崇められていることに憤慨していました。

He would often remark : When Rikyu was young his disposition was warm-hearted, but it is so no longer and he is quite a different person.

彼はしばしば注意を喚起して、利休は若い頃は熱い男だったが、そう長くは続かずに別人になってしまったっと批判していました。

A man's disposition changes every twenty years.

男性の気質は皆二十年で変わる。

I too from the age of forty felt an inclination to abandon self.

私も四十を超えて性格も落ち着き、自身を受け入れる様になった。

Rikyu has only experienced prosperity : he knows nothing of the reverse.

利休は成功を手に入れたが、その裏にあるモノを何も分かっていない。

The changes of the world and the vicissitudes of life are indeed more rapid than the shallows and deeps of the Asukagawa.

世の変化と人生の栄枯衰退は、あすか川の浅いと深いよりも急なのだ。

Therefore wise men will regard this phenomenal world as nothing but illusion, and wealth and position as mere passing clouds.

とにかく、成功を収めた人間はこの驚くべき世を認識もせず、幻想であるがゆえ、富と地位はただの過ぎる雲のごとくであるのに、、、。

I don't say that everyone should think thus, but only that thoes who understand these things will be secure, while those who do not will have trouble in the future.

皆がそうであるとは言わないが、未来にいたるまで揺るぎないモノだと信じ、災難に遭うことはけして無いと言えるとは思わない。

Kamo-no-Chomei moved his house about like a snail, and I, like a crab, live in a hole that another has made.

鴨長明はカタツムリのごとく住む家を変えた、私は一匹のカニで誰かが掘った穴に住んでいる。

Why should one trouble about fame and wealth in this transitory life?”

なぜ、ただ通過する人生なのに名声や富を求めるのか?

And truly he did not value these things.

彼はその事を解っちゃいない。

Neither did he defer to the rich and influential.

富とその先にある結果もどちらもうまく行きはしない。

At the end of his life he bought in all the poems he had written and burnt them : “So passes my elegance with my life,” he remarked, and so died.

臨終の時、彼は自身の詩を全部買い取り燃やしました。「時代おくれの己の優美さ」、そう言い残し死んで行きました。

It was so long after Hechigwan made this criticism that Rikyu received from Hideyoshi the order to put an end to himself, though, according to some accounts this was because he opposed Hideyoshi rather than flattered him.

その後、利休に対してノ貫が残した忠告は秀吉によって現実のモノとなりました。秀吉へのお世辞が反比例して怒りとなり、帳尻は元に戻ったのです。

When Hideyoshi was moving to the castle of Fushimi he impressed on each of his personal retainers the necessity of avoiding the use of the word‘Fire' on that day under the threat of a fine if they offended.

秀吉が伏見城へ移動した時、家来達が“火と言う言葉を禁句”とした命を実践し感銘を受けました。感情を害しない様に、仕えるとはここまでやらなければなりません。

After a while one of them, Maeba Hannyu, remarked :

前波半入が言っています。

“That was a very interesting Cha-no-yu that I attended a day or two ago. They used a wooden kettle.” “Oh, indeed,” said the Taiko, “and how did they prevent the fire burning it.”

「二三日前、面白い茶の湯に出席しました、木の釜を使っていました。」「なんだそれ?」っと太閤殿下、「どうやって釜が燃えずに湯を沸かすのじゃ?」

“Will your Highness be pleased to pay the fine? ”immediately retorted Hannyu.

「殿下の命令を違えてまで茶を楽めますでしょうか?」っと半入が即答しました。

“Dear me, dear me!” exclaimed Hideyoshi, scratching his head in amused vexation.

「忠勤!忠勤!」秀吉は頭を掻きむしり、歓喜し叫びました。